Karishma D’Souza | Anna Bella Geiger

Karishma D’Souza | Anna Bella Geiger

04.05.23 → 17.06.23

Anna Bella Geiger

Our latest exhibition opens a space for dialogue between two artists: Anna Bella Geiger and Karishma D’Souza. Although they belong to different generations, not to say different geographies, their poetic systems overlap in many ways. They do, for example, share a common obsession with territories and maps, whether those are contemporary cartographies or ancient mappa mundi, and take a map both as a noun and thus an objectified representation of a land or a globe, and as a verb, in a sense of a conceptual act of “mapping out new meanings”. Their practices are entangled with the idea of storytelling which doesn’t only seek to destabilize an established narrative (which both artists do), but also to gather, archive and protect different viewpoints in the carrier bag of history – and of fiction.

This understanding of a fiction as a recipient of the non-heroic and non-linear stories and originating from Ursula Le Guin’s essay “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” from 1986, seems to resonate deeply within the universes of the two artists. Just like Le Guin, both Anna Bella Geiger and Karishma D’Souza outline, in their own unique manner, an alternative to “a linear, progressive Time’s-(killing)-arrow mode of being”1 which speaks with ‘weapons’ and ‘wars’ far more often than with ‘words’. Likewise, they invite multiplicities of voices and visions into their systems of thoughts – to call into question things, structures, and ways of being. And, perhaps, it is through this multi-voiced kind of questioning, that our world, shaped by a logic based on domination and globalization, may evolve and transform. Bursting into new life rather than bursting at the seams (or into flames)…

Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1933, the daughter of Polish immigrants, Anna Bella Geiger has lived through dark political times, marked by censorship and dictatorship. It is thus hardly surprising that one of her main strategies has been that of the ironic twist, or that she should be interested in the concept of identity or rather identities (given her dual or even triple origins, if we take into account her Jewish ancestry, which obliged her family to emigrate in the first place, thus making her a “stranger” in her own country). Just like it is hardly surprising that another important theme for her has been the dichotomous relationship between the periphery and a center, artificially enflamed by geopolitical maneuverings. Advocating ideas of diversity and multiplicity as opposed to the uniformity and homogeneity of an authoritarian system, she has always sought to take a step to one side, to circumvent taboos and obstacles through the invention of new, labyrinthine pathways, where no-one could ever follow, since, inimitable, she has never really belonged to any artistic movement or group. She has also experimented with a wide variety of media, first switching from photography to printing, photocopying and collage, and then to painting and sculpture. Moving from one technique to another, she makes them intersect and intertwine, exploring their limits or boundaries, just as she would question the very idea of a boundary, whether political or mental, with a view to transgressing or redefining it. Nothing is fixed in her system of thought, everything is in constant flux, composing and recomposing itself. Unfolding layers and scrolls. Outlining new territories of meaning – to tell us stories, quite different from what we may usually hear.

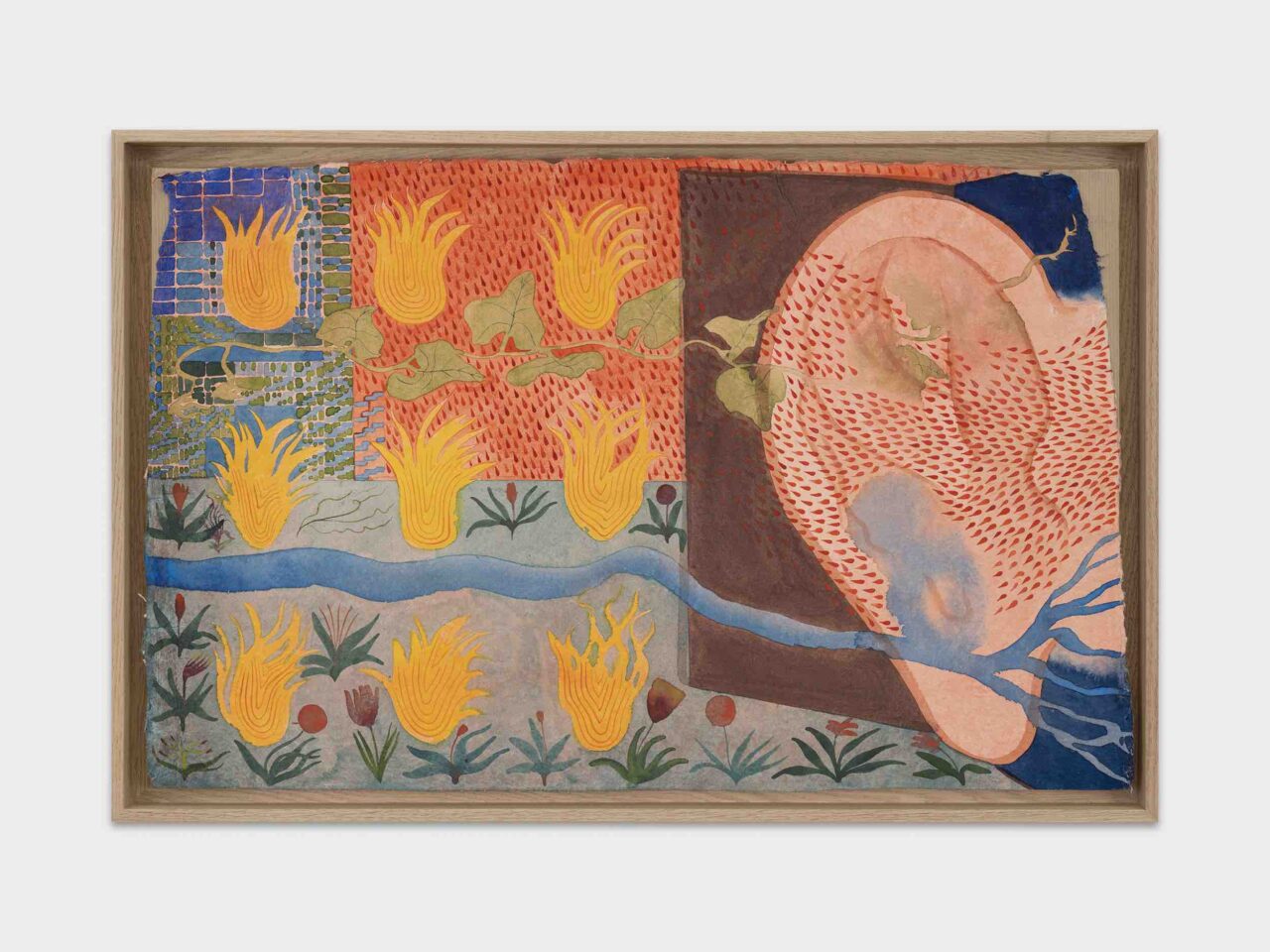

A map has been a signature element of her practice, but also its axis, both on the metaphorical level (since even during her visceral period, different from what we could see here, she laid out inner territories – and thus cartographies – of the human insides) and in terms of the technique. It has become something of a material: truly, a sort of materia prima. As she superposes, overlays and cuts into her maps and atlases, she “moulds” them as one might do with modelling clay or pastry dough, taking great care and rendering them malleable enough to be able to make something else. And whilst on the subject of pastries, the artist has indeed used cookie cutters to outline borders in her Borderlines sculptures. We thus move from the personal and intimate language of the kitchen towards the more “official” language of a public space, suggesting that both are political, as any choice or body or act is, even that of baking cookies, knowing that the most trivial and ordinary gestures can quickly become unthinkable if the ruling regime decides so. In the same way, maps of countries and viscera are naturally related, bringing geography and anatomy closer together, with this idea on the margins that a body, whether social or individual, physical or political, can be tortured and twisted – it can “bleed”. Anna Bella’s elegant and slightly chaotic soft paintings and embroideries, too, offer an escape from the modernist way of thinking, finding incongruous solutions and “indigenous” pathways which lead us away from rigidity of a structure or of a system, towards a fragmentary, less dogmatic and more flexible vision of a whole.

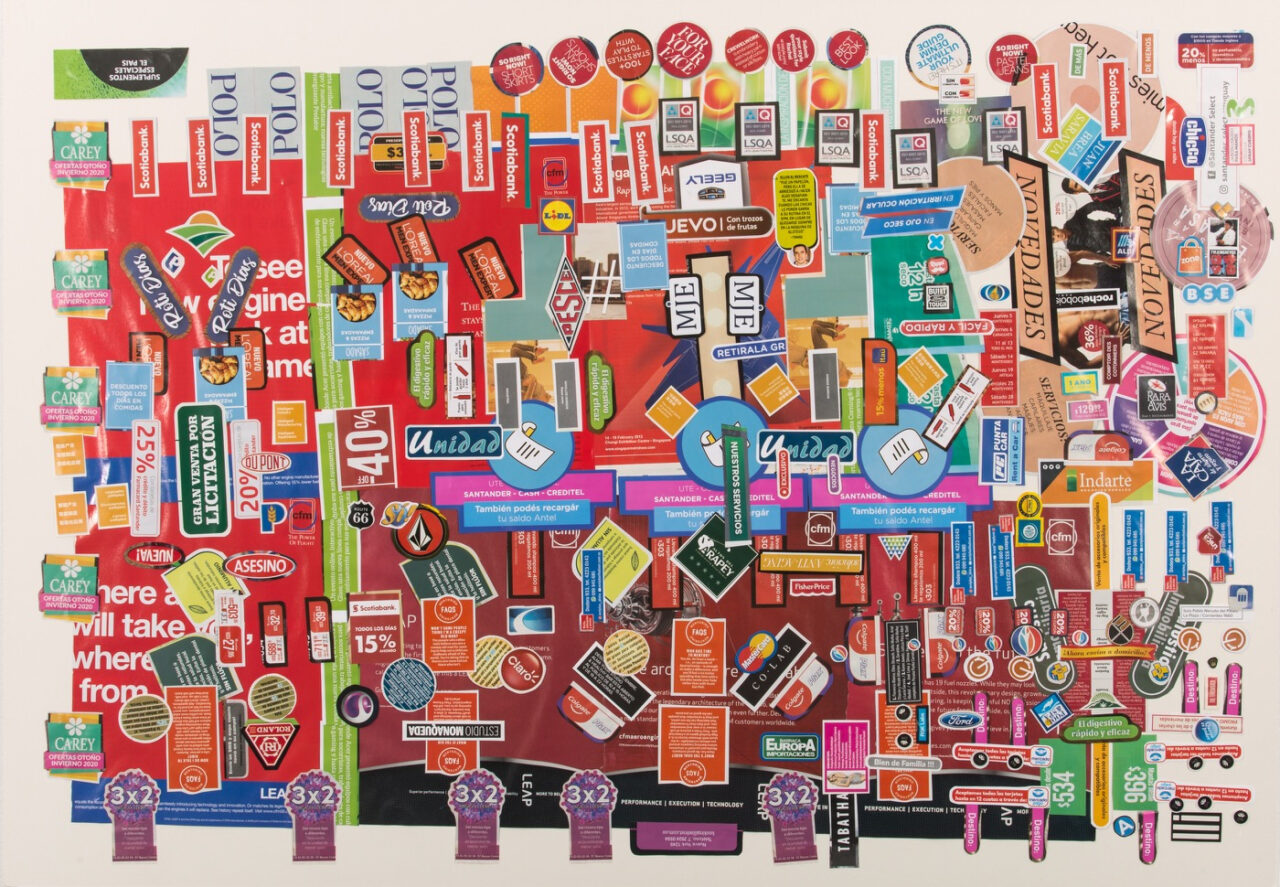

As for Karishma D’Souza, who was born in 1983 in Mumbai, thus 50 years and thousands of kilometers apart from Anna Bella, she has also been interested in interlacing political and poetical dimensions, sometimes openly, but more often in an allusive, encrypted way, for the viewer to unveil and to unfold. Her paintings and drawings are woven with symbols and signs, so that each object, each pattern, each vortex of shapes and colors is layered with meaning. Caught in a complex lattice of hidden references, just like a globe is caught in an invisible net of parallels and meridians, her works seek to capture the glimpses of the real, so that they could bear witness and record, gathering different stories and experiences, especially those that were silenced or remained unheard. Thus, they wish to make the invisible visible, to reverse the order of things, bringing some justice into it. A poetic justice, to start with.

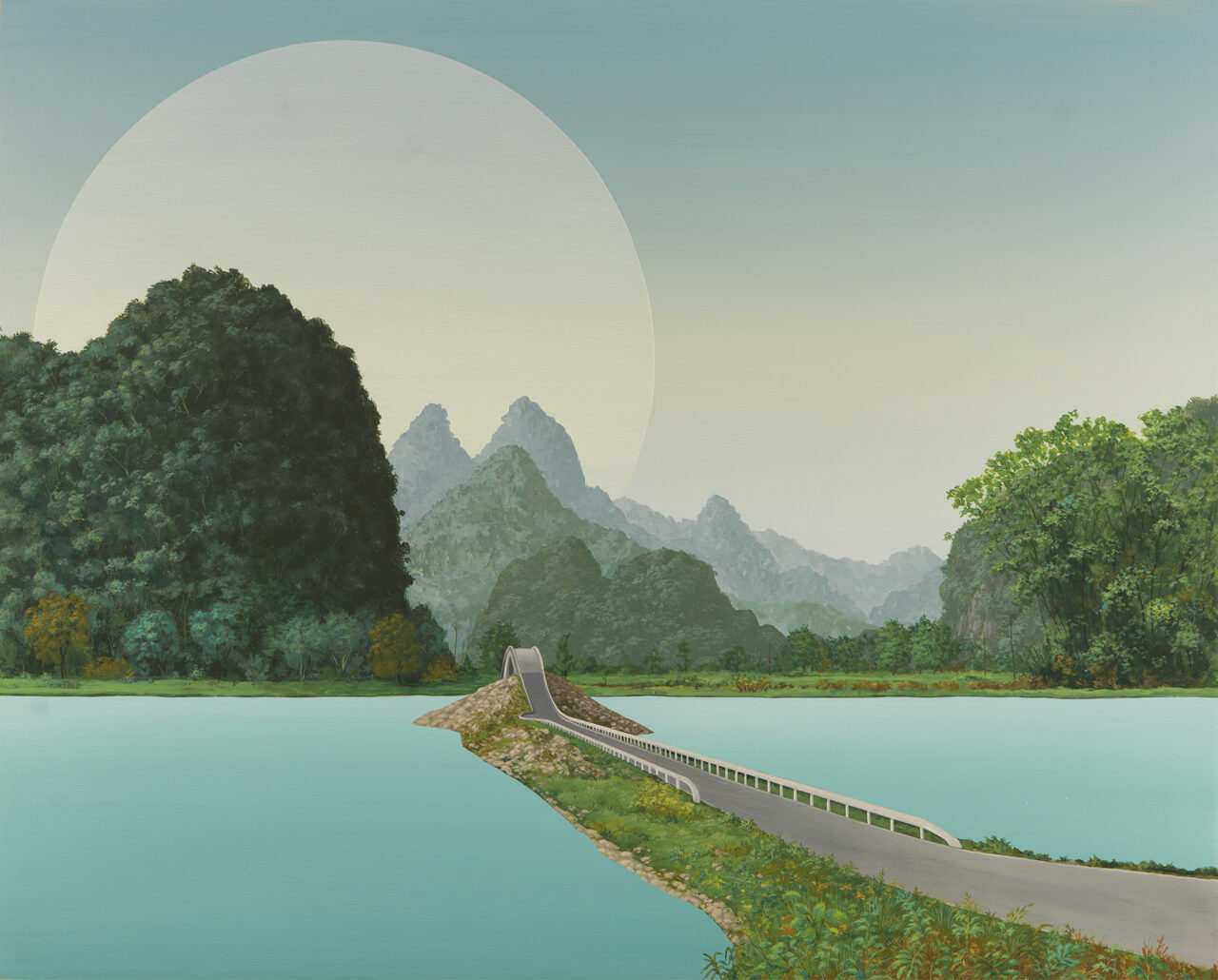

These bits of the real are often rooted in the political situation in India, whether it is the Hindu caste system, the oppressive ways of dominant culture resulting into a constantly increasing grip of propaganda, the ecological and economic crises, leading to the destruction of forests and to the eviction of native populations from the lands that they’ve cultivated for centuries and generations… Sometimes, they refer to the artist’s personal story, notably, to her moving away to Portugal, necessitating in her finding a way to inhabit and to encompass two parts of the world, two homes, two histories that are different but shared. To reflect, too, upon this two-folded experience, whilst moving back and forth. All this physical and mental travelling couldn’t but enable an important shift in her vision, an act of re-thinking and of re-valorization. Sometimes it is necessary to step back or to travel away in order to truly see the place one has left behind (just like in T.S. Eliot : “to arrive where we started / and know the place for the first time”2). It is then that one may understand how things actually work, looking through and beyond the official discourse, looking back with new eyes, that of a decontextualized stranger (although not really).

Of course, when T.S. Eliot (an important figure of reference for Karishma, alongside Namdeo Dhasal, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, Biblical parables, Robert Frost and many others) talks about this knowing of the place “for the first time”, what he has in mind isn’t really a physical journey, but rather a metaphysical one, which often moves in circles (and sometimes in spirals). However, in a way, each journey is metaphysical or at least could be. Notably, if it is mapped out through the movements of thoughts and inner currents (Journeys, 2018) – or if it creates space for a thought, encouraging us to turn our gaze inwards (Depth to recognize, 2018) – or if it allows to clear up a context to see (and to question) one’s roots – and see one’s inner secret schemes and private archetypes. In Witness (2020) and in the Portraits of parents (from 2019 and 2020), Karishma D’Souza seems to do exactly that: she clears up some space, whilst putting in motion a narrative of a desert. Thus, she comes over and over to this image of a vast space, of a wasteland, which is sometimes chaotically stitched from fragments, sometimes is filled with moving liquids, referring to inner movements in one’s soul. It is a space that is haunted by the memories and phantoms of the past – by all those eyes and faces of parents or friends – a space, where images appear out of nowhere as a mirage. Desert is a space for longing – for an abandoned place or for a deserted home, but it is also much more than that. It is a place one can fill with new images and stories, thus turning it into a “vast sack”, a “belly of the universe”, a “womb of things to be and a tomb of things that were”3. Into an unending story – a place where all narrative paths come from.

(1) Ursula Le Guin, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction”, 1986

(2) T.S. Eliot, “Four Quarters”, 1943

(3) Ursula Le Guin, “La Théorie de la Fiction-Panier”.

Exhibition views

-

![Karishma D'Souza-Anna Bella Geiger,Xippas Paris,2023_1]()

Karishma D'Souza | Anna Bella Geiger

Exhibition view, Xippas Paris, May 4 - June 17, 2023 -

![Karishma D'Souza-Anna Bella Geiger,Xippas Paris,2023_6]()

Karishma D'Souza | Anna Bella Geiger

Exhibition view, Xippas Paris, May 4 - June 17, 2023 -

![Karishma D'Souza-Anna Bella Geiger,Xippas Paris,2023_3]()

Karishma D'Souza | Anna Bella Geiger

Exhibition view, Xippas Paris, May 4 - June 17, 2023 -

![Karishma D'Souza-Anna Bella Geiger,Xippas Paris,2023_12]()

Karishma D'Souza | Anna Bella Geiger

Exhibition view, Xippas Paris, May 4 - June 17, 2023 -

![Karishma D'Souza-Anna Bella Geiger,Xippas Paris,2023_5]()

Karishma D'Souza | Anna Bella Geiger

Exhibition view, Xippas Paris, May 4 - June 17, 2023 -

![Karishma D'Souza-Anna Bella Geiger,Xippas Paris,2023_7]()

Karishma D'Souza | Anna Bella Geiger

Exhibition view, Xippas Paris, May 4 - June 17, 2023 -

![Karishma D'Souza-Anna Bella Geiger,Xippas Paris,2023_15]()

Karishma D'Souza | Anna Bella Geiger

Exhibition view, Xippas Paris, May 4 - June 17, 2023 -

![Karishma D'Souza-Anna Bella Geiger,Xippas Paris,2023_16]()

Karishma D'Souza | Anna Bella Geiger

Exhibition view, Xippas Paris, May 4 - June 17, 2023