Pauline Beaudemont – Salon des réalités nouvelles

Pauline Beaudemont

Salon des réalités nouvelles

30.01.15 → 14.03.15

Exhibition curated by Manuella Denogent

Pauline Beaudemont’s relatively young work has an air of permanence, of focusing on a particular notion, in this instance, of architecture. Or perhaps the latter is just the ideal format for a work that delights in evoking and bringing together references, not only artistic but cultural. And indeed, in the last few years, former photographer Beaudemont has adopted a multidisciplinary approach, calling on painting, sculpture, photography, video and installation.

Beaudemont’s exhibition, Salon des réalités nouvelles (lit. “Salon of new realities”) demonstrates her ability to mix sources and formats, filtering them through her own interests, architecture and popular culture – her other favourite subject. On this occasion, the artist will present three series of works, which refer to Le Corbusier’s work in Chandigarh, as well as Indian culture. These works follow up on a first series of videos, If You Put a Roof On… (2012), shot in the Villa Jeanneret-Perret, which the architect built for his parents in 1912, in la Chaux-de-Fonds, and where Beaudemont shot the performance of French dance hall queen AmZone – a rather unlikely encounter that could not have happened without the mediation of the artist.

The first of these series, Merci Charles-Edouard (Hinesh Jethwani studio) (2013), establishes the pictorial protocol that she has pursued in 2015 with two new paintings, Main Motive and Bhawan. The three paintings of the original series are each composed of a powerfully geometric form, on the surface of which the wood grain is visible, floating on an atmospheric monochromatic background. The sculptural element, however, remains silent, referring to nothing that can be identified, because here, in a way, the act of appropriation is happening during the production process, as the borrowed element is gradually separated from its source and the original meaning is erased, layer after layer, to the point of abstraction.

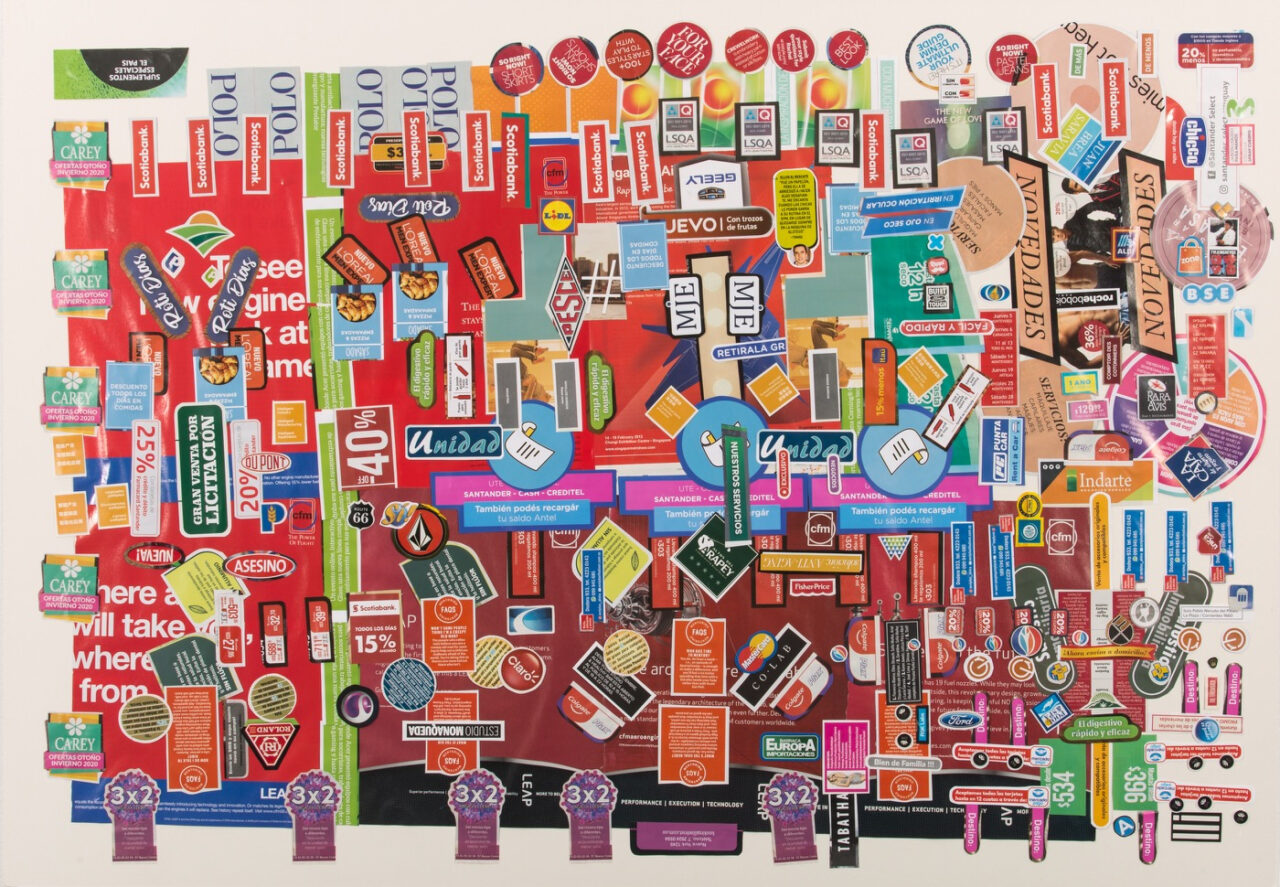

In concrete terms, the sculptural forms are derived from architectural details taken from buildings by Le Corbusier in Chandigarh, and transposed into teak sculptures that the artist had local craftsmen produce, based on her own sketches. She then photographed them and superimposed them by collage on photographs of Chandigarh, which she shot as she wandered the streets of the city. The collages were then entrusted to a studio of Bollywood poster painters in Mumbai who work manually using traditional methods.

It goes without saying that reproducing a photographic representation by painting, even realistically, constitutes a distortion of reality – the first step of which being the photograph itself. Entrusting a Bollywood poster workshop with the production widens the gap further still, the original subject being necessarily transfigured by an expressive form of craftsmanship usually dedicated to stars and glamour, much closer to post-war picture stories than to different variants of abstraction.

The Bhawan (2015) painting results from the juxtaposition of architectural elements that can be identified clearly, with interior details of the Gandhi Bhawan building (Gandhi’s home, which is now dedicated to the study of Gandhi’s work) in Chandigarh in the background. The presence, in the foreground, of a section of fluted columns floating in mid-air, with no relation to their environment, moves the painting closer to surrealist collage, and seemingly heralds (even if it remains ambiguous) the emergence of a symbolical dimension in the pictorial work of the artist.

The same dimension is at the heart of the Main Motive (2015) painting, which associates several symbolical elements pertaining to Chandigarh. Here, the open hand, the symbol of the city of Chandigarh (“open to all” as Nehru wanted it to be) is paired with the bird (the bird being an element of votive symbolism) of Dr N. Sharma. Sharma (still living in Chandigarh and whom Beaudemont was able to meet) was Le Corbusier’s first assistant on the Chandigarh project, before he became chief architect for the city. Inside the palm, the synthesised pattern of the chimney mantlepiece of Pierre Jeanneret’s house in Chandigarh is transformed into a symbolic pattern like the ritual Henna drawings that women adorn their bodies with in India.

The After Artémidore (2013) series, bearing the name of the 2nd-century Greek writer and founder of the science of the interpretation of dreams, associates architectural references with the artist’s own oneiric universe. On simple slabs of concrete, dyed in colours taken from Le Corbusier’s chromatic range, the artist has attached typewritten texts with uneven letters that betray the machine’s age. Beaudemont’s sleep is often somewhat disrupted by dreams. During her trip to India, Beaudemont sought to keep track of her most striking dreams by confiding them to paid scribes in the streets. As the artist tells her dream to the scribe, who then interprets it and transcribes it into somewhat broken English, the dream takes on a life of its own.

Under the finish of one of the green-coloured slabs, some marks appear in the concrete. They follow a detail of the “Modulor” drawing that Le Corbusier etched on the façade of the Chandigarh College of Architecture, as he did on all his most important buildings, a kind of manifesto for his style of harmony-based architecture.

The two Untitled (Chandigarh) (2013) videos, produced in association with Adam Bainbridge and filmed in the manner of a slideshow, reveal an outlook that is similar to a photographer’s. A sequence of pictures alternates between close-up static shots, almost abstract and punctuated with bursts of colour, and slow sweeping images of static landscapes. They paint the portrait of a city where urban disorder is juxtaposed with formally balanced architectural elements that exude an atmosphere of tranquillity. The compact cubic monitors are fixed on supports that the artist has created to form two small minimal and movable totemic sculptures dedicated to Chandigarh.

Finally Xippas Gallery presents a sculpture lamp from the artist, Béton-laiton (2015), recently produced by Hard Hat, the Geneva-based publisher of artist editions. It is made from a standard concrete slab, perhaps the most widespread model in the world, a simple brass sheet and a bulb. This construction (simple in its own way), made out of cheap materials used for construction work and decors, plays the porosity between furniture and minimal sculpture, and attest to the richness of the circulation of forms and signs.

It may be useful here to note that recycling strategies have dominated contemporary art since the 70s – a trail that was blazed by pop art, which itself drew from popular culture in relation to the then emerging “consumer society”. Of course, the borrowing phenomenon has always existed, but it is a defining feature of our post-modern epoch, touching the realm of culture as a whole, since cultural recycling is at the heart of socio-economic development itself. If a portion of art remains confined in its own borders (contemporary art recycling itself), other artistic proposals prefer to draw from the huge pool of cultural forms and signs, blurring and mixing temporalities and categories, as Beaudemont’s work does.

And yet the artist takes the recycling dynamic a step further, and that is precisely where her approach is particularly interesting and relevant, i.e. in including popular culture into her work (focusing on Eastern culture moreover) not only by borrowing but by entrusting the actual people in that culture with the realisation of her works.

The title of her exhibition bears the name of a salon of abstract art, which opened in Paris after the Second World War under the impulse of artists such as Sonia Delaunay, Nelly van Doesburg, Jean Arp and Pevsner, and which itself is derived from the expression Réalités nouvelles (“New Realities”), created in 1912 by French poet Apollinaire to define his own vision of contemporary society. These two dates more or less mark the beginning and the end of the era in which Le Corbusier worked and, more broadly, of the modern movement. The references that Beaudemont makes to the modern project, in which architecture played a major role, could appear as nostalgia for a time when a progress-obsessed society was brimming with plans for the future and able to project itself forwards. Alternatively Réalités nouvelles might serve to define the cultural paradigm of artists of her generation who, at the beginning of the 21st century, have opted for a form of generous syncretism, drawing from a variety of eras and forms of culture. And this curious and open eclecticism may well be a sign of resistance against global homogenisation.

Manuella Denogent

Artist

Pauline Beaudemont

Location

Rue des Sablons 6

1205 Geneva, Switzerland

Press release

Connect

Share